Tracking causes inequalities in education

February 27, 2018

![]()

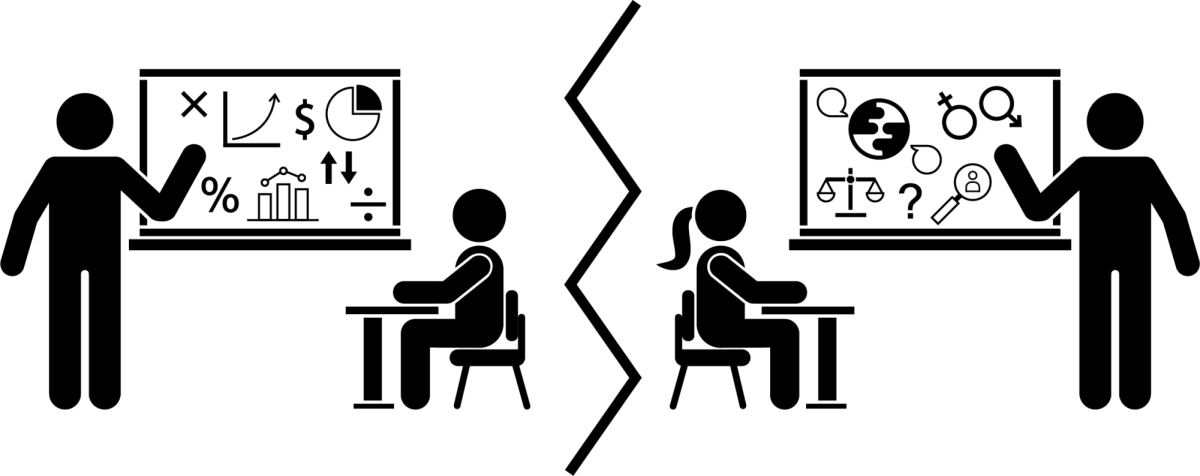

The GPA game starts long before students enter high school. Parents, teachers, and students push for tracking convinced that weighted classes lead to acceptance to better colleges. The process of placing students together based off ability in higher level classes such as honors or advanced placement can appear beneficial, but has underlying consequences that need to be addressed.

Tracking can begin as early as elementary school with classes like advanced math. Once a child is placed in an advanced track or in a regular track it becomes difficult for movement throughout the course of their academic career. It can even go as far to affect a student’s self esteem and ability to perform.

The best way to dismantle tracking is to prevent it as long as possible. Attacking it at its roots in elementary school and middle school by basing student placement on something measurable, not influenced by parental and student comments, and re-assessing students frequently and adhere to their personal needs.

One of the issues involving tracking is that by labeling students you affect the way they see themselves. In the book “Detracking for Excellence and Equity” by Carol Corbett Burris and Delia T. Garrity, they explain how language can affect a student’s self esteem. They detail when teachers use comparative language, “low” kids versus “advanced” and “average” kids versus “gifted”, a sense of superiority and inferiority is created. Kids in honors classes feel pressure to live up to that expectation versus kids in non-tracked classes feel diminished and unworthy of the resources provided to them.

I have taken mostly honors and AP courses since freshman year, and it has been brought to my attention that teachers refer collectively to honors or AP classes as “overachievers” or by addressing us collectively “oh you’re honors kids” as reasoning to give us less guidance. Due to this language, it’s easy to adopt the mindset that I’m in some way better than students in classes ‘lower’ than mine. I’ve had conversation with friends in non-weighted math classes that will dismiss problems or accomplishments I have in school by saying “yeah, but you’re an honors kid.” This type of conversation creates a divide and limits conversation about the one thing that all teenagers have in common, school, creating the misconception that just because someone’s in a different class than you means that they can’t understand you.

I realized that I only know a portion of my graduating class because I’ve been in classes with the same kids since elementary school. The problem with tracking is that it secludes groups of students, often minority groups, limiting interactions between them.

As a senior in high school, I finally had the flexibility to choose a non-weighted English class to take for fun. To my disbelief walking in first semester to my Voices From the Edge class, an elective English class, I was shocked to find that I either didn’t know the students around me or I hadn’t interacted with them since elementary school. I’ll admit that it wasn’t run like the English classes I experienced in my previous years at school, but there were opinions about politics, family, drugs, friendship, and lifestyle that I never would’ve been exposed to in an honors or AP class because the diversity simply wasn’t there.

It can be said that it is unfair to high achieving students to be placed with students with possibly more behavioral issues or students who need slower-paced lessons. Therefore continuing to track students based off ability will produce an overall higher number of higher performing students.

However, simply producing more students who are higher in math isn’t solving the problem. Students who have been marked as underperforming students can become stuck in the lower level tracks even after they’ve matured and their abilities have changed.

A study done at Stanford University by Sanford Dornbusch revealed that of the students mis-assigned to lower level classes, 30 percent were minority groups (African American and Hispanics) and about 13 percent for Caucasian groups.

A lot of minority groups are unfairly placed in non-weighted tracts which continue to isolate them. All students are capable of greatness and it’s unfair that minorities aren’t given the same opportunities because they’re placed in lower level classes at the start of their high school careers.

Burris and Garrity argue that students deserve access to equal educational opportunities. Sorting students based on test scores and other criteria is an unequal practice. Their suggestions for detracking involve specific guidelines for lesson planning and classroom arrangement that directly attack inequality. This would be achieved through training teachers to address instructional needs based on how the individual performs in class and not on assessments.

To further prevent inequality, we should delay tracking in schools until sophomore year. This way students can learn to communicate with one another and elevate one another in a mixed classroom full of different personalities, demographics, and intelligence.