Eliminating toxic stigmas around men’s mental health awareness

January 24, 2023

Men’s mental health awareness has been in the spotlight of social media, with athletes and celebrities like Michael Phelps and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson sharing their personal struggles with mental health to their audiences. Instagram posts and stories by accounts like “@worrywellbeing” and “@projecturok” highlight important statistics and resources for men who may be struggling. Accounts like these exist all over Instagram, with over hundreds of thousands of followers, and are using their platform to bring awareness to the topic to men all over the world.

Locally, athletes at DGN take to Instagram to share their stories of personal mental health struggles. In January, DGN Alumni and University of Wisconsin-Platteville football player Timmy Ryan took to Instagram to share his story with his peers and followers. Ryan detailed his post with examples of how he struggled day-to-day with pressure within sports, school, and everyday tasks.

“[Mental health] is absolutely not talked about in sports enough,” Ryan said. “Very few professional athletes have come out and shared their mental health struggles with the world, but when they do, they make a large impact. When I posted on my Instagram about my depression and anxiety, I intentionally put photos of me playing football in the post for two reasons: I love playing football, but I also wanted to inspire other athletes to be more open about their mental health. It’s an uncomfortable thing to do, but at the end of the day, having a support system helps so much, and they can support you so much more when they know what you’re going through.”

Like Ryan, University of South Carolina baseball commit and senior George Wolkow took to social media in November 2021 to highlight to his followers, ‘it’s more than just a sport’. Wolkow and other local athletes urged followers to get help if they needed it in honor of Ryan Jefferson, a junior at Providence Catholic High School and University of Illinois baseball commit who died by suicide in November 2021. The hashtag ‘#RJ3’ was created in honor of Jefferson and contained hundreds of athletes sharing their stories and encouraging followers to speak up about their mental health struggles.

“As an athlete, mental health is huge for performance and work ethic,” Wolkow said. “Days when I am feeling great always lead to productive, consistent training. Days when I am upset or struggling often lead to a bad workout or an inconsistent schedule. An unhealthy mind blocks me from peaking while playing [baseball] or training, and it prevents me from being myself on the field.” “If men can break the stigma around ‘struggling,’ then millions of athletes can begin to perform better.”

Athletes find comfort in confiding in coaches and mentors, who help to normalize mental health struggles and fight negative connotations to encourage their athletes to speak up. While not all coaches promote this environment due to existing stigma, Defensive Coordinator Keith Lichtenberg ensures his football players are doing well on and off the field.

“For kids who are going through something, one thing I like about sports is it’s a huge network of support around them,” Lichtenberg said. “For any student athlete that is going through any time of mental health struggle, we [the coaches] like to be a place where they can come and talk to us. I think sports give students an outlet to share if they’re going through struggles or challenges, whether it be on the field, or another issue in their own personal life.”

Along with student-athletes, male students in other extracurriculars such as band, choir, and theater also struggle with mental health issues and describe the struggles of getting help as a man. The pressure to meet everyone’s expectations during performances overwhelm students involved in the arts.

“Doing so many things at once at North has gotten a hold of me mentally a handful of times,” junior Matthew Sirota said. “I would definitely say that the build up to a [theater] production can be a very stressful and overwhelming time, but most often I find myself breaking through that anxious haze and feeling most confident and proud by the end of each one. It gives me something to focus on and work on while also testing my ability to adapt and develop in different situations. The day of [the production] is definitely when those feelings reach a climax, but they very quickly dissipate.”

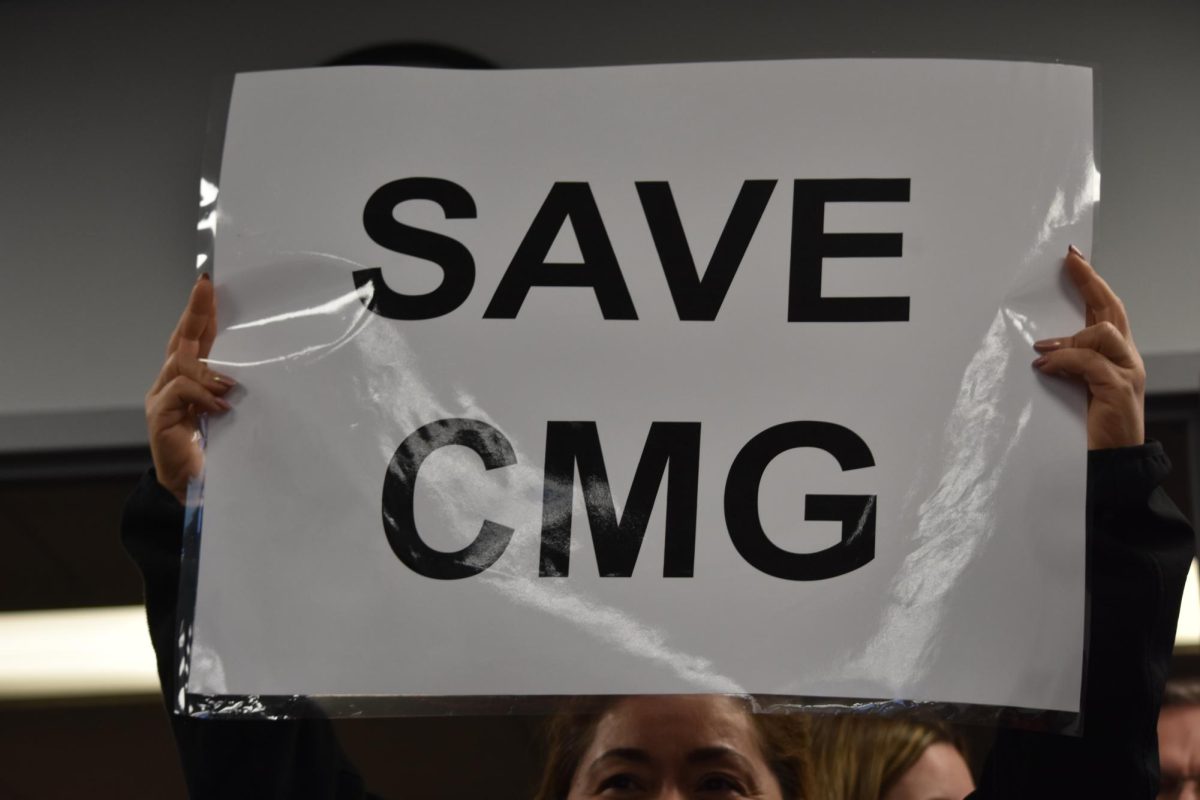

Students also recognize mental health help resources at DGN, and how they are a reliable, accessible way for men to get help directly through school.

“I think as a community at DGN, we do a pretty good job with handling men’s mental health,” Sirota said. “The CSSS department tries their hardest to advocate for all people, but the issues generally occur when the individual themself does not seek help. Society as a whole needs to start tearing down these stigmas and stereotypes of confident and toxically masculine men in order for students and males in general to feel that they can take the initiative to seek help.”

Some males describe getting help as ‘dreadful’ or ‘unhelpful’, alluding to the problem that causes mental health issues to go untreated in many young men. According to Mental Health America (MHA), men are less likely to get help because when asking for help, it’s viewed as a sign of weakness. This can lead to under- or mis-diagnosis.

“Getting professional help can be a huge challenge for anyone,” senior Jon Isoniemi said. “I have known a handful of young men who have severely struggled with mental health issues, and seeking help was completely out of the picture.”

As someone involved in both athletics and fine art activities like choir and theater, Isoniemi recognizes that the stigma surrounding mental health exists in many environments, all at once.

“Mental health isn’t discussed enough in any community, and men don’t want to talk because it appears as a lack of independence, and a weakness. It’s hard to say what will change that because it’s so much more complicated than it seems. Talking is complicated when no one wants to speak,” Isoniemi said.