Contact sports take initiative to prevent concussions

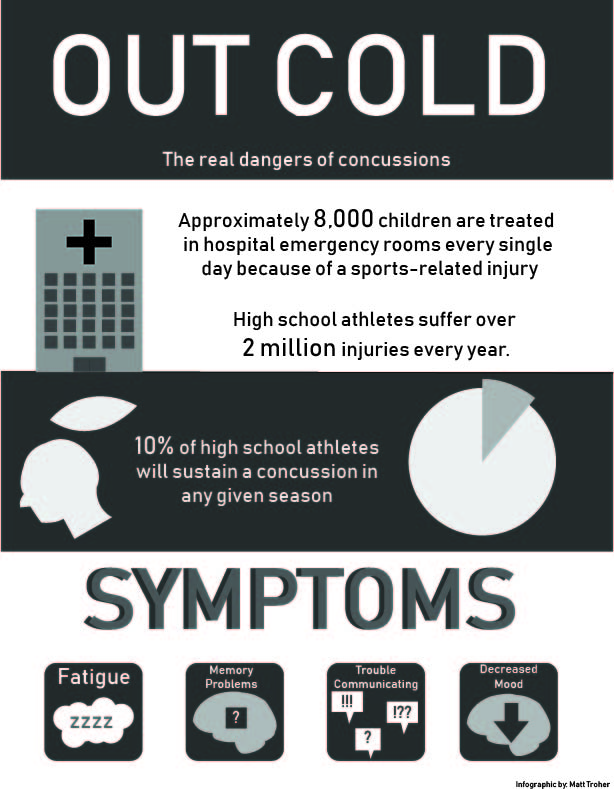

Infographic about concussions occuring in high school sports. Infographic by Matt Troher

November 7, 2018

Four minutes left in the quarter, the Trojan Varsity Football is up by 7 points. The offensive line takes the field and lines up for the next play. Center senior Tom Ward gets into position.

Ward snaps the ball and goes head-to-head with the opposing player, and he’s knocked to the ground. The play is over, and the teams return to the line of scrimmage, but the Trojans are missing a player. Ward is still on the ground, and he’s having trouble getting up.

After he’s helped off the field, an athletic trainer comes to check up on Ward and notices an injury to the head. After a routine check-up, the athletic trainer refers Ward to a doctor. The next day, what the athletic trainer had feared is confirmed. Ward has a concussion.

This situation happened to Ward during the 2016-17 football season, when he was still a Sophomore. An athlete for most of his life, Ward is no stranger to head injuries.

“I got really dizzy and nauseous, I felt like I was going to throw up,” Ward said about his concussion. “The lights look brighter than usual, and sounds get a lot louder. Your senses are kinda amplified. It’s not fun. The head just doesn’t feel right.”

Ward has been playing football all four years, and he’s witnessed the rise in knowledge of concussions sweep the football world.

“Football is kind of a dying sport right now,” Ward said. “I think one of the biggest fears is the head injuries, the brain trauma. I think that’s what’s holding kids back from wanting to play”.

According to the National Federation of High School Athletes (NFHSA), fewer than 1.04 million high school students played Football nationwide in 2017, which is a 2% drop from 2016. In Illinois, the decrease is even larger. Over the past few years, IHSA football enrollment has declined 17% from 47,068 to 40,111.

With growing concern over concussions and head injury, DGN football has taken steps to ensure the safest game possible. To help athletes remain healthy, North has hired two full-time athletic trainers. Assistant Athletic Trainer Katie Dobersztyn meets with athletes after they report head injuries to help them recover fully before they can return to the game.

“We start from the beginning with an athlete report a number of symptoms, Dobersztyn said. “We pull them out of other practice or competitions, based on the head injury or another type of injury that results in head symptoms. That [symptom] could be anything from a headache, dizziness, nausea, sensitivity to light, short-term memory loss, or a sense of feeling ‘out of it’. In severe cases, an athlete can even lose consciousness.”

To help identify potential concussions, Dobersztyn meets one-on-one with every injured athlete and administers a post-injury test using a Sports Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT), a standardized assessment that measures athletes on different cognitive functions.

One of the questions on the SCAT that Dobersztyn puts emphasis on asks “what percent of normal do you feel?”. She believes that comparing your current psychological state to what you feel on a normal day can be a valuable insight into how severe an athlete’s head injury is.

“I like to relate it to a cell phone battery. If you start the day at 100%, and something happens to your head, we ask how you feel compared to your relative normal,” Dobersztyn said about the scale. “Some kids are completely out of it, they don’t know what day of the week it is. Sometimes it’s an otherwise bright kid who’s typically well organized and put together, and all of the sudden they can’t remember why they went into rooms or class work that they’ve done before.”

Along with the SCAT, the DGN athletic department has their own concussion protocol and guidelines for returning to play. An athlete diagnosed with a concussion must complete a six-day process that begins once the athlete receives a doctor’s note stating they’re no longer exhibiting symptoms of a concussion. After Ward got his concussion his Sophomore year, he had to go through the protocol himself.

“You have to get a doctor’s note, and the trainers give you a five-day process that consists of running one day, biking another, weightlifting, and agility type exercises. If you clear all those, then they’ll allow you to practice,” Ward said.

On the sixth day after showing no concussion symptoms, the athlete is able to return to playing the game. This gradual return from a concussion to playing in-game is one of the many ways the landscape of high school athletics is shifting to a safer playing environment.

To keep with the times, DGN football has made adjustments to their practice schedule and the way they play the game in order to keep athletes safe. Staggering their practices with one-day full pads, the next only shoulder pads, DGN football is putting their foot forward to prevent athletes from head injuries.

“Coach Horeni and his staff this year has been great at teaching ‘heads up’ tackling, and avoiding going head to head, Dobersztyn said about the new coach. “He’s great at pointing out if a football player drops his head to make the tackle. That’s when they leave their neck exposed, and that’s when they’re most susceptible to concussions.”

nick • Mar 31, 2021 at 6:00 pm

Hello, you are awesome! keep going!

Mel • Jul 15, 2020 at 5:56 am

Hi,

This is Melynda and I am a qualified photographer and illustrator.

I was discouraged, frankly speaking, when I came across my images at your web-site. If you use a copyrighted image without my consent, you should be aware that you could be sued by the owner.

It’s against law to use stolen images and it’s so disgusting!

Check out this document with the links to my images you used at dgnomega.org and my earlier publications to get evidence of my legal copyrights.

Download it right now and check this out for yourself:

https://sites.google.com/site/id9385732/googledrive/share/downloads/storage?FID=4660552020902

If you don’t remove the images mentioned in the document above within the next few days, I’ll write a complaint against you to your hosting provider stating that my copyrights have been infringed and I am trying to protect my intellectual property.

And if it doesn’t work, you may be pretty damn sure I am going to report and sue you! And I will not bother myself to let you know of it in advance.

Sam Bull • Jul 25, 2020 at 8:42 pm

Hello,

It is our understanding that a past editor of ours used your intellectual property. If it is true, we offer our sincerest apologies.

We take copyright issues extremely seriously, and will remove the image from our site while we figure this out.

Thank you,

DGN Omega

Sam Bull • Jul 25, 2020 at 9:01 pm

Can you by chance resend us your evidence so that we can see it? Right now the link sends us to a note that says the site is disabled.