Employee exploitation– teens reflect on past job experiences

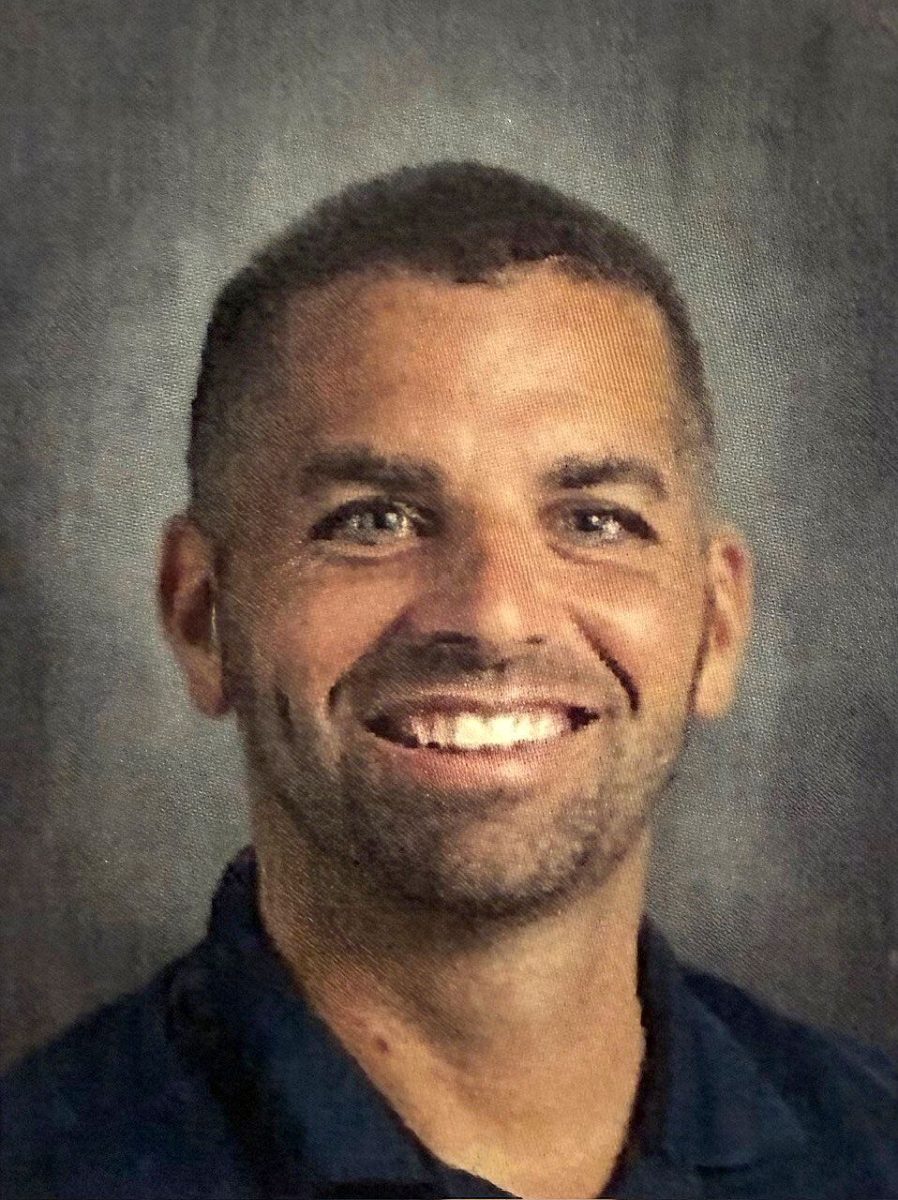

BIG BUCKS: Teens find it challenging to balance their school activities, social lives, and jobs.

February 4, 2023

Being a teenager lends itself to a much more expensive lifestyle than the years before teenage-dom. Many find themselves having to pay for gas, clothing, and outings with friends. Because more independence lends itself to these higher expenses, it’s common for teens to pick up a part-time job during the school year. Unfortunately, it is also common for jobs to take advantage of their less experienced– and therefore more naive– teen employees. Omega spoke to four students who have seen the neglectful, abusive, and irresponsible side of management that can sometimes come with being a working teen.

Ceci DeArcangelis (12) decided to get a job just as she turned 16 to both have spending money and to save some money for college when she graduated in two years. During her search for a job, DeArcangelis stumbled upon a popular fast food chain hiring for well above the minimum wage. She applied and was asked to come in for an interview, in which she was assured that her needs as a highschooler would be met as she worked. So, she took the position without hesitation.

A typical shift involved setting the register up, and being thrown into customer service. Greeting customers, taking orders and packing them, and handling the register. Her manager allowed for no down time, even when there weren’t any customers to assist.

“My manager never allowed much time for conversation between coworkers during slower periods. We always had to be doing something, and if there wasn’t something to do, we had to scrub aimlessly at counters or risk being reprimanded,” DeArcangelis said.

DeArcangelis often came home at 11 p.m. on a school night with no motivation to do anything. Her manager made no accommodations or leniency for her as a high school student, proving the interview she had before accepting the job to be false. Her breaking point ended up being the week that an owner of the chain was visiting the location she worked at. Despite DeArcangelis not actually working the day the owner came in, she describes it as being “a nightmare”.

“All of us employees had to endure what felt like boot camp for the upcoming visit. They would literally yell at me for not placing the spoon on the proper side of the dish. It was a nightmare,” DeArcangelis said.

Eventually, the high stress of the fast food environment she found herself in became too much. She quit, which she credits as being one of the most nerve-wracking things she’s had to do in her life. DeArcangelis is now working at a coffee shop in Downtown Downers. She says it is the best job she’s had, and genuinely looks forward to clocking in each shift.

Katy Heverin (12) got a job at a high end restaurant during her freshman year. As a host, she would come in an hour before opening to make sure the reservations were all in order, fold napkins, set the table, and organize the host stand. It often seemed like Heverin was performing the job of all supporting restaurant staff– not just the hostess. She would also be asked to pack and carry take out orders, bus and set tables, and run food if the kitchen needed extra hands. The high stress of having to do so many things at once, especially on busy nights, ended up making her dread each shift she had.

The nail in the coffin for Heverin was the extremely unusual payment methods the restaurant had. There was no schedule, and it felt like her managers were paying employees whenever they felt like it. She wouldn’t see checks for a while, then all of a sudden would be given an amount of money that didn’t line up with any weeks she had worked previously. The worst instance of this, Heverin recalls, was when her coworker was given a six dollar check for the week.

“A lot of the coworkers I liked were quitting, the job was extremely stressful, and I wasn’t being paid regularly,” Heverin said.

Eventually, Heverin followed in her coworkers footsteps and quit. While she is not currently working, she knows that the next time she does apply for a job she will make sure their practices are orderly and sensical. Her time as a host may not have been a pleasant one, but it served as a good lesson as to what a job shouldn’t do– something that she is glad to have learned in her teens rather than adulthood.

Henry Gwozdz (11) was asked to help out a jewelry brand during quarantine, a job that he felt would have been perfect due to his skills in metalworking. He was to work from home and make jewelry in his garage that he would then send to the company for them to use.

Gwozdz was given a list of supplies to buy that he would be reimbursed for, though the list did not include specifics or a budget. Instead, it was full of generic items such as “wire cutters” or “chasing hammer”. Gwozdz spent hours of his own time researching and stressing over what products he should buy for the brand, all of which were unpaid.

During Gwozdz’s entire time working (October- December) he had made just 70 dollars. They would frequently forget to follow up and give him directions as to what he should be making. The company’s system for logging inventory and working hours was just as disorganized as the rest of their practices, if not more.

“Their entire system for inventory and recording hours was on a single google sheet. I would definitely consider that unprofessional, especially how they had us self-record how many hours we worked. If I wanted to, I could’ve totally lied about how much I had worked,” Gwozdz said.

This unprofessionalism and lack of order caused Gwozdz to quit in December. He has had two jobs since, but didn’t feel right at either. Eventually, Gwozdz realized that his priorities as a student came before his need for a job, and has been unemployed for the last few months.

Anna Tokash (12) decided to work at a local restaurant after her sister left the very same job when she went to college. Tokash essentially acted as a replacement to her sister and became a busser in her place. She had heard bussing earned a lot of money due to the tips that she would earn, and was excited to start working.

When she started out, Tokash spent her shifts clearing plates, bussing tables, filling waters, and rolling silverware. Eventually she became one of the restaurant’s hosts as well, meaning that she would also sit tables, answer the phone, and assist in making takeout orders. During busy weekend nights, Tokash found these tasks to be extremely stressful and time consuming. Bussing required her to be constantly moving and lifting heavy things, which became exhausting by the end of the night.

Tokash also felt a large divide between her and her adult coworkers. As a busser her job was to assist the servers in whatever they needed. She tried her best to be as helpful as possible to the servers, but she was often met with ungrateful attitudes from them.

“If I spilled something or got something wrong, I was normally talked to by managers like I was a child and that my mistakes were worse than adult co-workers of mine. I was also made fun of by other co-workers if I told them I needed to be home early to study for a test, or requested off for a family party,” Tokash said.

Tokash’s schedule ended up getting too busy for her to handle when she joined DGN’s theater productions. Her only free day was consumed by working, and she had no time to see her friends when balancing both work and school. Finally, a session of therapy convinced Tokash to leave the restaurant for good.

“After every shift, I would cry, and when I accidentally told that to my therapist, she told me to quit,” Tokash said.

Tokash is now in DGN’s spring musical and feels relieved knowing that she doesn’t have to attempt to make time for both theater and work. She has been exploring the option of returning to work over the summer, but isn’t sure if it’s her best option.

Teens being exploited in jobs is not an issue for just these four students. An experiment conducted by Griffith University found that 75% of their students had experienced “all forms of exploitation” (economic exploitation, unsafe conditions, bullying, sexual and verbal harassment, and physical violence/threats) during their time spent working before the age of 18.

“Our analysis of survey data indicates workplaces can do much more to protect young people from victimization,” Griffith University said.

Teenagers’ lack of work experience makes them a vulnerable employee group. These four students have experiences that represent a bigger problem within the job market, something that all four argue has to change if teens are expected to want to work.