Addressing the elephant (and donkey) in the room: Capitol insurrection spurs larger discussion over nature of political conversation in school

A Nov. 2 study* conducted by the Pew Research Center shows that 89% of Trump supporters and 91% of Biden supporters said they disagreed on basic facts, and another Pew survey, this one from Nov. 6, reports that four out of five Trump and Biden supporters disagree not only on policy but also core American values and goals.

February 8, 2021

One month ago, a mob of Trump supporters stormed the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. in what has come to be known as “the insurrection.” Later that night, Principal Janice Schwarze began formulating the district’s response, meeting with social studies chairperson Michael Roethler to put together a presentation for his department and sending an email out to all teachers.

“As you prepare for classes tomorrow, remember that as educators, we cannot take a political stance with our students, and we should not share our opinions or provide an interpretation of the events,” the email stated. “However, we also should not ignore current events. In fact, our Social Studies teachers are preparing for conversations with students over the next few days. Talk about a teachable moment!”

Schwarze elaborated on her stance in an interview with the Omega, explaining that staying neutral and presenting information in a non-biased manner is crucial in order for students to draw their own conclusions.

“Teachers have to stay non-partisan, so they can’t take a side. When they are sharing or having conversations with students it’s very important for them to be impartial and to not say, ‘this side was wrong,’ or, ‘this is what you should believe,’” Schwarze said. “So, teachers should be presenting all sides of an issue and asking questions that will get students to draw their own conclusions and providing sources for them so that students can base it on fact.”

THE CAPITOL RESPONSE

Some, however, while agreeing with the value of facilitating non-partisan discussion, felt that the incident at the Capitol in particular was beyond the realm of politics. Equity and Inclusion Council member Joann Purcell explained her point of view and what was discussed at the Council’s meeting shortly after Schwarze’s email to the teachers.

“I get why an administration would tell us not to discuss [the insurrection] because I think a lot of people have very polarized views on it at this point. So, I get it as a parent, I get it as a math teacher why I should not, say, in October, talk about the election…” Purcell said. “What the problem was in this meeting was that we on the Equity Council felt that it wasn’t a political stance, it was something that was wrong.”

“I don’t know how I could address this at all, acknowledge it, and not show anger and frustration and sadness at what happened,” Purcell added. “And so, I thought the message that we got was, again, to not share our feelings. Which I get in every other situation, but in this situation, I feel like no one can do that. No one who has an ounce of self-awareness could talk about this without showing some emotions.”

The morning after the incident, Roethler held a meeting with DGN’s social studies teachers to outline the department’s plan for addressing it in classes. Social studies teacher Keith Lichtenberg elaborated on why he thought that meeting took place.

“For me, there were really two reasons [for the meeting]. Reason number one is that these are uncharted waters; none of us there could say, ‘Oh, this is just like this event, let’s teach how we did before,’” Lichtenberg said. “But also number two is that our role as teachers is to inform and not indoctrinate, and so to make sure that we’re all teaching from the standpoint of fact, the standpoint of trying to de-escalate tensions versus pouring more gasoline on the fire.”

Despite the work behind the scenes, neither D99 school released a statement to the student body. Schwarze explained that this was due to the Capitol incident revolving more explicitly around political ideologies.

“We made a statement about all of the Black Lives Matter protests… because we felt that we have students in our school who look like some of the people who have been persecuted, right? They need us to stand up and say, ‘this is not okay,’” Schwarze said. “That was clearly about people and targeting people of color; it wasn’t Republican or Democrat. So, we had to say, ‘That is not okay. This is about humanity. This is not okay.’ So, then we can make a statement. The attack on the Capitol was a little bit different because that was political.”

Schwarze added that while she described the incident as political, she also said that there were racial and discriminatory undertones present such as certain shirts that people were wearing, the police presence in comparison to Black Lives Matter protests, and police actions in both instances. It was her hope that students would bring those ideas up in classroom discussions and it wouldn’t be something that teachers or administrators would be initiating.

“All of those things—that should come out naturally in the conversation, it shouldn’t be the teacher coming in and saying this, this, this, and this. Those are things that people brought up and that’s what we want,” Schwarze said.

That next day, discussions regarding the incident ensued in some classes. Lichtenberg explained how he approached facilitating discussion in his class to maintain an unbiased viewpoint.

“I have no problem telling my students that I was horrified, disgusted, and frustrated by the events that I saw on Jan. 6. But [that’s] not a political statement of it’s Trump’s fault or it’s the rioters’ fault, or it’s the Democrats’ fault for allowing the steal to happen,” Lichtenberg said. “No, it’s just saying, ‘Look, I think everyone in their right mind agrees that we don’t want people breaking into our nation’s Capitol, smashing glass and putting people in harm’s way…’ we don’t want that to happen—that’s not a political statement. However, what led to that and what has been a result of it, politics fills the air.”

Senior Sara Sheikh had a less optimistic view on the nature of DGN’s in-class discussions of the event, explaining that such a monumental event should have been addressed in the moment as well as after—no matter the class.

“We spent only like 30 minutes discussing the Capitol incident even in my sociology class. It’s like you’re sitting there in math class while the entire government is under siege and we’re not watching the news?” Sheikh said. “It’s teaching people that they should be ignorant of the news if it doesn’t affect them. I feel like in a school setting if something so monumental is happening then we should spend time focusing on those issues—it’s more important than other things in the moment.”

ESSENTIAL CONVERSATIONS

For English teacher Michael Tompkins, political discussion “absolutely, undeniably” has a place in classes other than social studies courses, and while the desired amount of political discussion in class varies widely for each student and teacher, he believes there are certain conditions needed in a classroom in order for effective political discussion to occur.

“Educators have responsibilities dealing not only with their content but with their student body in their classroom. And that’s a professional judgment that they ultimately have to make based on all sorts of sort of intangibles: who’s in their class, what’s the tenor of their class like, where are they in their curriculum, how does a [political] discussion at this particular point either fit or not fit appropriately kind of an academic purpose,” Tompkins said.

Social Studies teacher Amy O’Dell, who teaches Multicultural Studies, noted the value of political discussion in the classroom, explaining that it not only informs students but allows them to interact with unfamiliar opinions and situations.

“You can’t even number the benefits of [political discussion in school]. This is why social studies classes are so important because they teach students how to empathize with people, to navigate these conversations and to deal with situations that make you uncomfortable,” O’Dell said. “That’s what’s beautiful about social studies classes… I don’t like making students feel uncomfortable, but I do teach in areas of discomfort.”

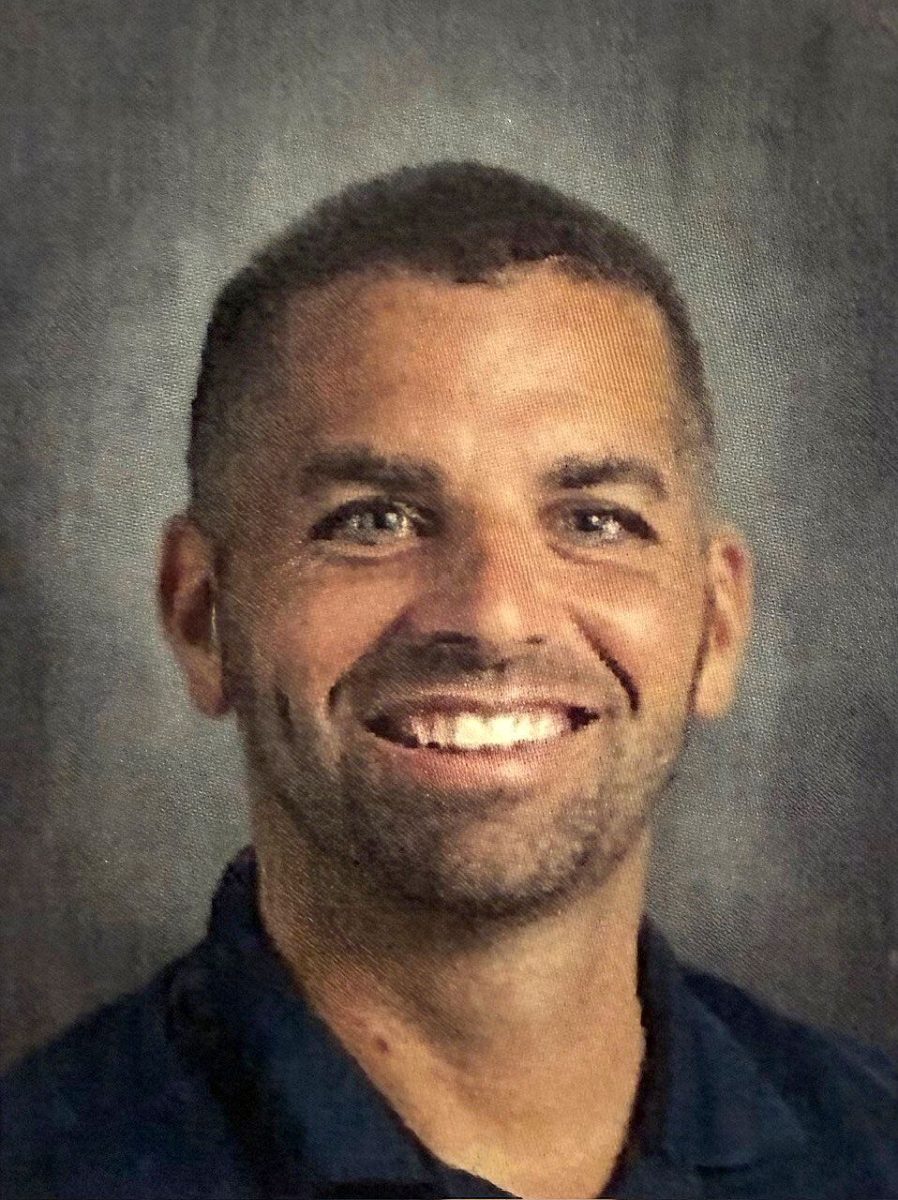

Social studies teacher Michael Pacer expressed similar notions, explaining how he makes it a goal as a teacher of Contemporary American Issues to not only encourage political discussion but also guide students down a path that entails respectful and fact-based conversations.

“I think that sometimes we rely too much on social media or major news networks or getting only one side of an issue or [being] unaware of issues completely. Our goal is to make you, one, more aware of the issues so you can formulate your own opinion, and, on top of all that, be able to discuss it appropriately, respectfully, and with facts,” Pacer said.

OVERARCHING FLAWS

Still, some, like junior Lincoln Peckenpaugh, believe that political discussion should have a greater role in high school education than it does now.

“I just wish it was more incorporated… like just last Wednesday with the mob attacks on the Capitol, there were a few teachers that I had that brought it up, that incorporated it into… the beginning of class, and we need more of that because the more awareness that can be brought to different issues in the political world, the more aware people will be,” Peckenpaugh said.

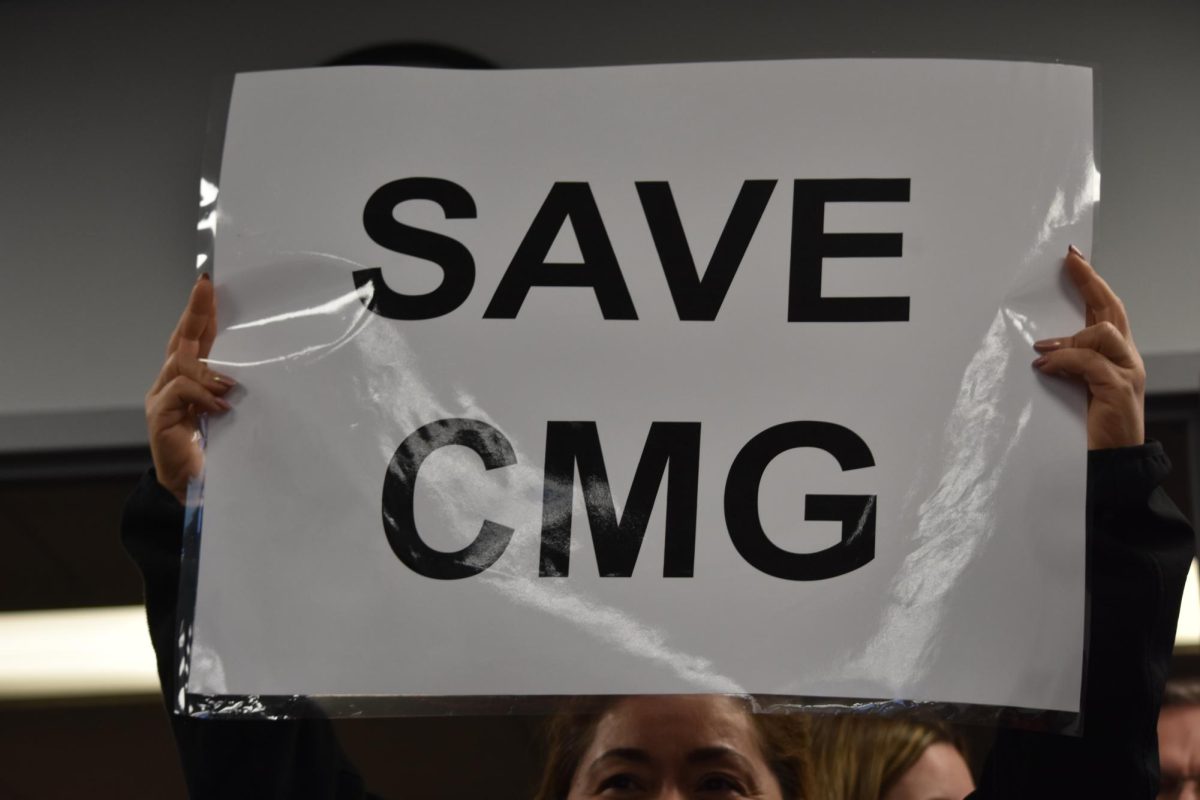

Sheikh had a similar point of view, explaining how social studies courses, and Global Connections in particular, should be restructured to talk more about political and social issues.

“I think that they need to stop dumbing it down and trying to protect our feelings and they need to teach it more for real. In Global Connections in particular we shouldn’t learn so much about random things like pillars: I still know the pillars but I don’t know about so many more important issues,” Sheikh said. “I think we just need to reassess what’s important to learn and we should have more discussions on political and social topics and issues because it’s important.”

Some see problems with the nature of political discussion at DGN in a different way: sophomore Ryan Dennison expressed how he feels many teachers only display one side of the story.

“I think it just makes [students] feel a certain way about what [teachers] say, and [students] might agree on it because they don’t hear the other side; all they hear is what the teacher has to say,” Dennison said. “If they only hear what the teacher has to say then they are not getting [to hear] the other side so they don’t know where the other side is coming from. So I think it’s a little unfair because I think you should see both sides of every story.”

“Sometimes I feel like teachers like to sway the students and make little short comments that grab the students’ attention and make them feel one way or another about things, so I think it’s a little unfair, especially because they are all on the same side usually,” Dennison added.

To allow more balanced and diversified conversation, junior Connor Moore hopes that students will take it upon themselves to understand their political views outside of school in order to promote more productive discussion in class.

“I think that politics are not talked about enough at school,” Moore said. “I wish that more people would do actual research themselves without just repeating or reposting what other students have said. Also, I wish that more people spoke up from both sides of the political spectrum because this would lead to more interesting dialogue that is less one-sided.”

THE BIGGER PICTURE

Purcell expanded from the nature of political discussions at DGN to that of the nation, noting that this time of stark divide across the country takes a toll on the younger generations.

“I hope that this [divided climate] isn’t the situation for the rest of your lives and my kids’ lives because it’s a lot more stressful. You guys don’t have a frame of reference because you don’t really remember when it wasn’t this stressful,” Purcell said.

Nationally, the divide between Democrats and Republicans appears to only be growing. According to a Nov. 2 study* conducted by the Pew Research Center, 89% of Trump supporters and 91% of Biden supporters said they disagreed on basic facts. Another Pew survey, this one from Nov. 6, reports that four out of five Trump and Biden supporters disagree not only on policy but also core American values and goals.

With a high amount of fundamental disagreement throughout the country, O’Dell believes that viewing issues from a moral standpoint can make them more approachable and easier to discuss and talk about.

“There are no two sides to racism, there are no two sides to when a bad thing happens. We can talk about a bad thing because it’s a bad thing,” O’Dell said. “And so I think we as a society like to put that under the umbrella of politics… I think that it’s important that we call out bad behavior for bad behavior and not call it politics because they’re different things.”