Need for answers spurs ADHD diagnosis

February 15, 2017

Face it: high school is a tough place for kids. But when you layer in a behavioral disorder like ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) or ODD (Oppositional Defiant Disorder), things get a lot more difficult.

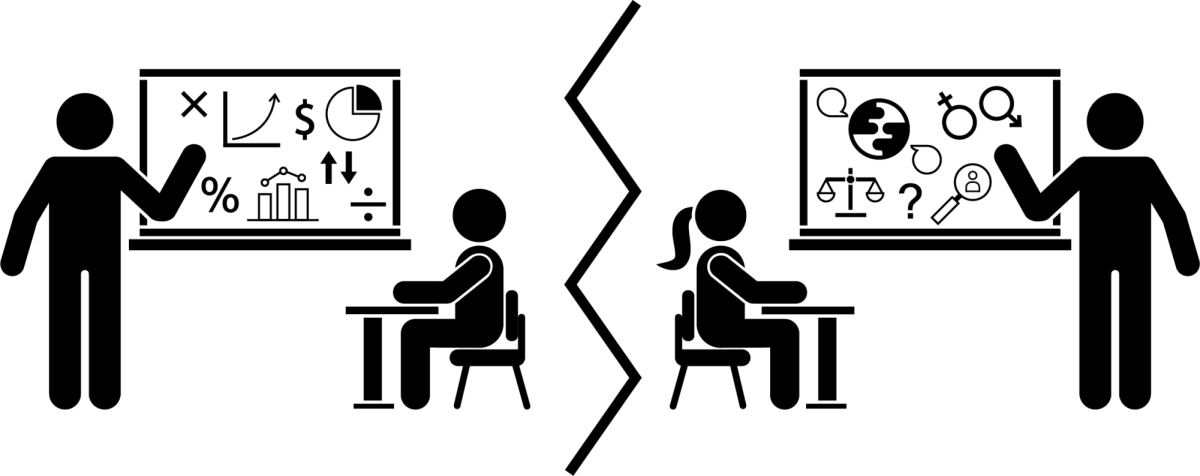

Students who deal with these disorders can experience difficulty concentrating, controlling impulsive behaviors, or following directions, all of which doesn’t add up well in a regimented and standardized school environment.

“I space out with teachers who just talk,” ADHD-diagnosed freshman Gianna Turner* said. “Teachers that just teach by lecturing make it hard for me to learn.”

However, programs can be implemented to help students like Turner. One such measure is an Individual Education Plan (IEP), a document drawn up with parents and counselors which details special services that a student must be provided with to ensure their academic success. But according to a 2015 study of childhood behavioral disorders by the School of Health Policy and Management, that is where a complication arises.

“Concern for inappropriate diagnosis of ADHD in children exists, and substantial controversy exists regarding correct diagnosis of ADHD,” study conductor Dr. Polly Ford-Jones wrote. This ease of misdiagnosis opens the door to parents looking for an explanation for a child’s erratic behavior.

“It’s easier to think that something’s wrong surface-wise, like ADHD, than to think that things are about anything else,” mother of sensory processing disorder-diagnosed child Jena Abrahamsen said. “That dissolves a lot of blame in some ways.”

Abrahamsen, who is also a DGN English teacher, noted that “parents can gravitate towards a diagnosis because it is a clear-cut thing: a factor out of their control.” The actions of their child need not be closely examined to truly understand what is happening.

“By making an ADHD diagnosis, we ignore and stop looking for what is really going on with the child,” psychiatrist Peter R. Breggin said. An issue outside of a diagnosis could be a lot more nebulous than simply slapping on a label: problems at home, other emotional issues, or social issues that a parent might not be privy to can contribute to the matter.

Championing a diagnosis, however, is a double-edged sword: Abrahamsen, due to her parental status, should know.

“As a person who has a child with special needs, I was going to the school a lot for evaluations. I kept hearing an ADHD diagnosis, but I knew it wasn’t right: it’s just what we know best. ” Abrahamsen said.

Even though the behavior exhibited by parents looking for an explanation adds another layer of difficulty onto a teacher’s job, it stems from a place of deep love; they want to take some kind of action to help their child, even if it isn’t the right one.

“[Parents] are trying to jam a square peg in a round hole, but at least they’re jamming that peg,” Abrahamsen said.

Parental education plays a key role in whether a kid gets the help they need. If parents are not aware of what’s negatively affecting their child, they might default toward a presumptive diagnosis of a behavioral disorder.

“It’s really important that teachers use affirming statements to parents who are having these issues,” Abrahamsen said. “Because even if they’re misdiagnosing it, the misdiagnosis could turn into the proper diagnosis if the teacher is paying attention.”

Even if parents default to an ADHD diagnosis, they’re ultimately reaching for help. Will teachers have the requisite compassion to reach back and help them find the truth behind the misdiagnosis?

*A false name was used to protect this student’s privacy.