Students’ rights to freedom of speech within schools

December 17, 2020

The first amendment protects the right of every American citizen to think and speak freely and ensures the promise of freedom of expression. In a school environment, freedom of speech is safeguarded for students to prevent interference with the school’s educational mission.

The U.S Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that public school officials can regulate and limit student’s freedom of speech they view as disruptive. However, numerous Supreme Court cases have outlined the types of freedoms students do have, creating new boundaries of freedom of speech within the school system.

Tinker v. Des Moines (1969):

In Dec. 1965, a group of students attending a public high school in Des Moines Iowa wore black armbands in a silent protest against the Vietnam War. The principals of the Des Moines school created a policy against the protest, in which a refusal to take off the band would end in suspension.

The Supreme Court ruled in a 7-2 decision that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”, taking the position that school officials could not restrict speech based on suspicion that the speech possibly could disrupt the learning process.

The Tinker v. Des Moines Supreme Court ruling was the historic decision that cemented students’ rights to free speech in public schools, allowing students to express their opinions without disrupting the educational process.

“I want kids to express their opinions. I want them to do it in the right setting. In the right way and listening to other views about controversial issues,” social studies teacher John Wander said, “you don’t have to agree with them but you have to respect their opinion.”

New Jersey v. T.L.O (1985)

In a New Jersey high school bathroom, two students were caught smoking cigarettes by a teacher. One of the students immediately confessed to smoking, while the other student, T.L.O., denied any of the allegations.

The administrator at the school accused T.L.O. of lying and ordered to see her purse, where they found cigarettes and cigarette rolling paper which was used for marijuana, wads of money, and a list of student names who appeared to owe her money.

The case was taken to the Supreme Court and a 6-3 vote in favor of the school was made, deciding that the search of T.L.O.’s purse was not in violation of the 4th amendment. The Court held that the fourth amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures also applies to the conduct of public school officials.

In cases of social media and the internet, there are a lot of unknowns because technology is changing so rapidly. If there is a disturbance outside of school hours it is possible that school officials could be notified, and punishment could vary depending on the case.

“When it comes to instances of harassment and online bullying, social media is fair game. Meaning that, if something happens on social media outside of school and school hours, if it’s impacting the school day, students could be punished for their behavior,” social studies teacher Amy O’Dell said.

Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986):

During a high school assembly, Matthew Fraser presented a speech for a student-run government position. In his speech, Fraser alluded to graphic sexual references and was ultimately suspended for two days for his language use.

In 1986, The Supreme Court decided in a 7-2 decision in favor of Bethel School District, finding that the school is allowed to prohibit the use of vulgar and offensive language.

“[The Supreme Court] ruled that his speech was not protected under the first amendment right,” social studies teacher Erin Moore said, “the school does have the right to protect the values and the public education, and so therefore when he gave a speech like that, the first amendment would not cover that.”

The Supreme Court also concluded that school administrators and officials could limit the freedom of speech if it goes against the “fundamental values of public school education.”

“When someone would say something that would violate that, the school has a right to take away that person’s freedom of speech,” said Moore, “basically saying that person doesn’t have that freedom of speech in schools that would go against or violate what the school values and promotes.”

Morse v. Frederick (2007):

In later cases, such as Morse v. Frederick (2007), the Court rejected the student’s claims and outlined the importance of public school’s values and virtues.

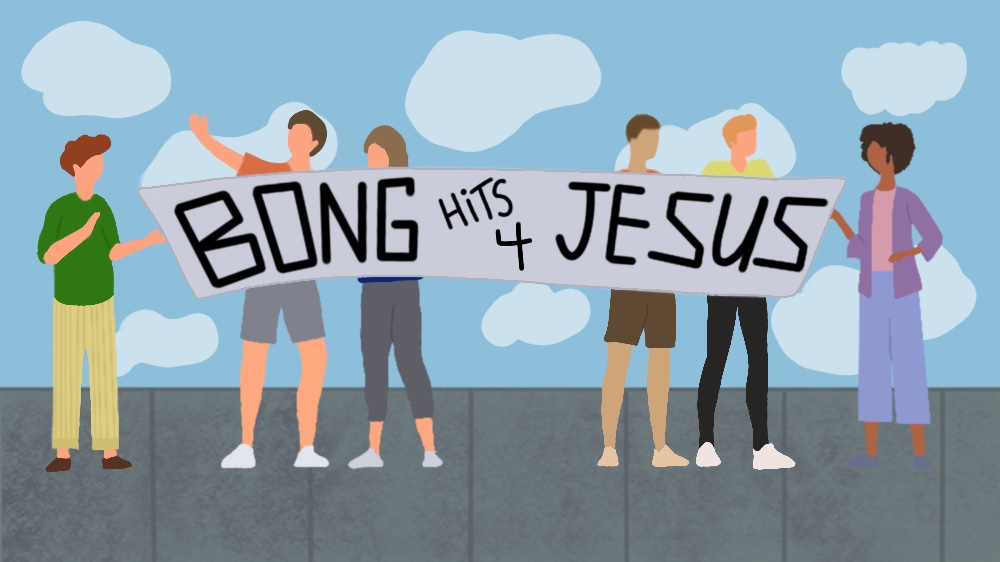

Jan. 24, 2002, Joseph Frederick held up a banner with the sentence “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” displayed during the Olympic Torch Relay for the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. Frederick refused to lower the banner after being reprimanded by school principal Deborah Morse and was suspended for 10 days for violating school policy.

The Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision Frederick’s first amendment rights were not violated and that schools may take away the freedom of speech to safeguard those entrusted in their care.

“It shows you a precursor of how events that are not directly in the classroom or in the school can still come back, and the school still has the ability to hurt that speech or issue punishments for,” social studies teacher Keith Lichtenberg said, “just because you can say it in the comfort of your own home or on the street does not mean that it should be said or can be said in a school environment.”

The Morse v. Frederick final decision allowed the limits of freedom of speech within school grounds or on school-sanctioned events, either if it’s disruptive or not.

“So let’s say that someone posts something and it is inappropriate but the school never finds out about it and it is not impacting the educational environment, we cannot do anything about it,” social studies teacher Karen Spahr-Thomas said, “the other thing about it is, it is not the quantity of students it affects. If it affects just one student and disrupts their learning, and we can establish that nexus, then we can impose discipline or consequences.”

* This article was written in response to an email regarding the racist incident by Principal Janice Schwarze on Nov. 18. The Omega will continue to provide coverage of this incident with additional perspectives from students and teachers later this week via dgnomega.org and corresponding social media platforms*