ARE WE ONE?

School requires parents’ signature to share her sexuality on We Are One DGN announcements

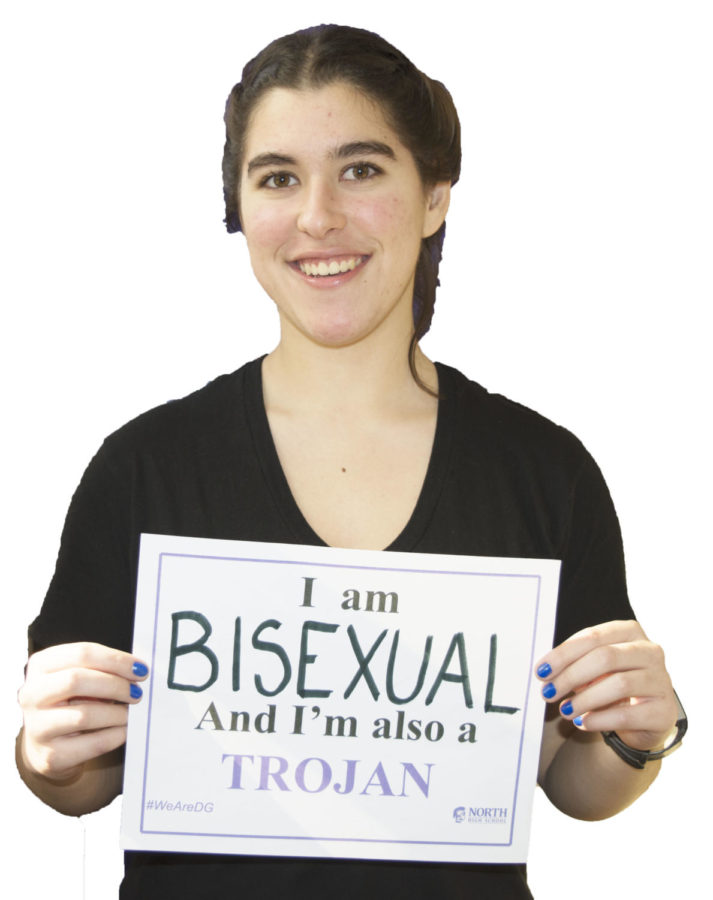

SHARING HER STORY: Selma El-Badawi (12) poses for a staged photograph holding a sign displaying her sexuality.

February 22, 2018

During the Friday, Jan. 26 video announcements, a segment from the “We Are One” diversity group aired. In this clip, group members held up a sign which stated “I am [blank] but I am also a Trojan,” with students instructed to fill in the blank. Senior Selma El-Badawi volunteered to participate in the video. She filmed a segment, and her sign said: “I am bisexual, but I am also a Trojan.” El-Badawi’s clip did not air.

El-Badawi was invited to the “We Are One” group in the beginning of the 2017-18 school year when Principal Janice Schwarze approached students with various backgrounds.

“I invited some students that I knew who had talked to me about making the school more inclusive than previous years. My goal is that we would represent as many different diverse experiences as possible but also have some students that represented very much the mainstream experience,” Schwarze said.

The initial planning for the video segment took place in November of 2017, after students spelled ‘ONE’ on Carstens Field. Due to final exams taking place at the end of December the video was pushed to second semester. El-Badawi and other students in the group were asked to take part in the video segment.

“We were told pretty repeatedly by Mrs. Schwarze and Mr. Mirandola that we should make it something meaningful. Don’t have it be something like ‘I’m on track’ or ‘I’m in this’, because a lot of the building is in that stuff. It was supposed to be something that clearly emphasizes our divisions but also brings us together,” El-Badawi said.

On Jan. 22, the filming day, El-Badawi and other students wrote on their signs a word or phrase that represented themselves. El-Badawi said that Schwarze saw what she wrote, and did not say anything. Due to this El-Badawi assumed what she wrote was fine.

The next day, Schwarze found El-Badawi outside of her first period class and struck up a conversation. El-Badawi said that Schwarze made note that she saw what was written down on the sign, and was confused about whether or not it could be shown on the video announcements. Schwarze told her that in order to have her clip broadcast, Schwarze would have to have a conversation with her parents to make sure they were both aware of El-Badawi’s sexuality and comfortable with their daughter participating in a video about it.

Later on Jan. 23, El-Badawi went to her social worker for advice on the situation. The social worker advised El-Badawi to speak with social studies teacher Lois Graham and English teacher Missy Carlson, both of whom would know more about El-Badawi and the situation.

As the day went on, El-Badawi was called to Schwarze’s office during fifth period. This time, Schwarze arranged a formal meeting in a conference room. During the meeting, Schwarze informed El-Badawi that the decision to require parental consent was to protect the school in case of legal trouble.

“As a school, we have to follow federal law and we have to make sure that we protect our students as much as possible,” Schwarze said in an Omega interview on the matter.

In El-Badawi’s case, her mom and step-mom are aware that El-Badawi dates both genders, but her dad is still unaware of her sexual orientation. El-Badawi lives in Downers Grove with her mother. Her father lives out of state.

“My father is not really aware, but my step-mom is. I live with my mother though, so I don’t really see the point in him knowing or needing to know. With my mom, I’m kind of out, I’ve never explicitly said that I’m bisexual, but she knows that I’ve kind of dated boys before and girls before,” El-Badawi said.

Despite her mother’s knowledge of her sexuality, El-Badawi still felt that the school’s order to have an official conversation with both her parents was wrong.

“I felt like them calling my parents, first of all, will be making a big deal about it to my mother, and second of all, it would actually be outing me to my father,” El-Badawi said.

Instead of giving Schwarze permission to have a conversation with her parents, El-Badawi decided to remove herself from the situation, and her video from the segment.

“I’m between a rock and a hard place, and I decided to just leave. I told them that I’m not doing the video,” El-Badawi said.

Later, on Jan. 23, El-Badawi contacted Illinois Safe Schools Alliance, which is a non-profit organization to help LGBT+ students. Illinois Safe Schools Alliance has been involved with the school before, most recently with the addition of gender-neutral bathrooms.

“I felt like I was in over my head, and I just wanted to know what my rights were. I knew the Illinois Safe Schools Alliance could help me,” El-Badawi said.

Nat Duran, Young Engagement Manager at Illinois Safe School Alliances, advised El-Badawi on what to do.

“I suggested Selma try to get a meeting scheduled with the principal and any additional needed supports at the school and offered to participate via phone. I also asked if it were possible to invite a community partner into the conversation who may have stronger relationships within the school’s regional community,” Duran said.

On Jan. 24, Schwarze contacted Illinois Safe Schools Alliance. A meeting was held on Feb. 8, via phone, regarding El-Badawi’s situation. Duran believes that lawyers view students under the age of 18 as having less rights than students who are 18.

“It became clear that principal Schwarze was following the recommendations made by the school district’s attorneys. I offered best practices per Alliance values, which prioritizes youth-led processes and self-determination.” Duran said.

The district law firm, Franczek Radelet, advised Schwarze and D99 that El-Badawi’s situation could be a violation of the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA).

According to the U.S. Department of Education, PPRA is “a federal law that affords certain rights to parents of minor students with regard to surveys that ask questions of a personal nature.”

The PPRA covers eight topics, ranging from political affiliations to income status. In an Omega interview, Schwarze made it apparent that she believes El-Badawi’s situation falls under section three, pointing to the area ‘sex behaviors or attitudes’ on the PPRA document.

“If it’s a red flag here [in the PPRA] then it’s probably a red flag in other areas too,” Schwarze said.

Omega has tried to contact the district’s law firm regarding the definition of “sex behavior and attitudes”, but they could not give us the information “due to legal policy.” As for how the law may be interpreted, law teacher Karen Sphar-Thomas gave her insight.

“Because of how [PPRA] is stated, it lends itself to multiple interpretations of what it means. Therefore, the district’s law firm can interpret it in their own manner, whether students, or others, may or may not agree with that,” Sphar-Thomas said.

The Student Press Law Center (SPLC), a non-profit organization which specializes in advocating for student First-Amendment rights, often deals with issues of student censorship. Omega contacted the SPLC to ask for their interpretation of the PPRA. In an email, senior legal consultant Mike Hiestand clarified how PPRA applies to El-Badawi’s situation.

“While the PPRA restricts school officials from asking such questions without parental permission (such as in an official school survey), it in no way prevents students from volunteering personal information (including sex behaviors or attitudes) about themselves. Students, including student-edited media, are not subject to PPRA’s restrictions,” Hiestand said.

The video announcements aired on Friday, Jan. 26, with no trace of Selma’s video. Despite pulling out of the segment nearly a month ago, El-Badawi, along with others in the school, still carry on the conversation.

“When I go out into the world [my sexuality] is always a question. When I’ve dated girls I have always been cognizant that not everyone accepts this and not everyone is going to have the same opinion as me, but I can’t really let it hold me back. I am going to live my life and do what makes me happy, and I’m sure there are plenty of other things that I am going to do that people don’t agree with, so why let this stop me?” El-Badawi said.